Originally Featured in The New Yorker By Brent Crane

On a sunny January morning outside Richmond Hill, Georgia, Bill Eberlein, a fifty-two-year-old former I.T. specialist, went diving in a local creek. He wore a wetsuit, a drysuit, a dive hood, and an orange kayaking helmet affixed with a waterproof headlamp, whose ten thousand lumens would afford him six inches of visibility under the murky water. Eberlein—soft-spoken, blue-eyed, big-bellied, with curly dark hair and a long face—had worked this stretch of creek bed before. He has devoted the past eight years of his life to hunting, collecting, and selling the fossilized teeth of the Megalodon, an immense species of prehistoric shark. His destination, a depression forty feet down into the flowing ochreous void, had in the past proved a honeypot. Now, as usual, he would have to search it using only his gloved hands. “Every once in a while you grab something and it moves,” he told me, with characteristic blasé.

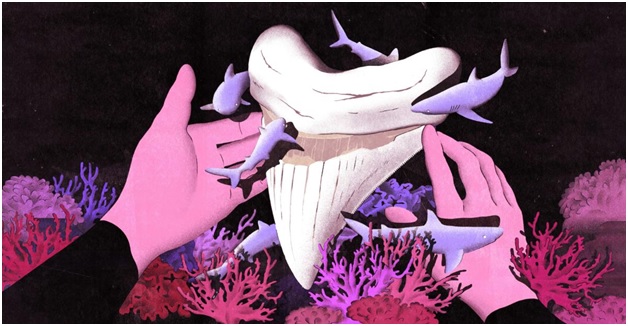

When picturing the Megalodon, whose name in Greek means “big tooth,” it is easiest to imagine a modern great white, only four or five times more great. Megs, as collectors call them, could grow as long as sixty feet, making them the largest known sharks in history. They lived between twenty-three and 2.6 million years ago, well after the dinosaurs and well before humans. Their distribution was global—teeth have been found on nearly every continent. But, beyond that, according to Kenshu Shimada, a professor of paleobiology at DePaul University, “There are a lot of things that we still don’t know.” Sharks’ skeletons are made of cartilage, which degrades easily, so questions like what the Megalodon ate, what, precisely, it looked like, and why it went extinct are difficult to answer. Its teeth, fortunately, age well, and are common along low-country coasts from North Carolina to Florida.

Meg teeth are triangular in shape and viciously serrated, ranging in color from sandy brown to dark gray. Most are between two and five inches long. Bill Barker, who used to hawk fossils on QVC, told me that they first became commercially popular in the nineteen-nineties. Today, the teeth are typically sold online, where they may fetch anywhere from thirty dollars to thousands, depending on their size. Eberlein’s most prized tooth, a 6.92-incher that his wife calls the Beast, was once appraised at fifteen thousand dollars. (He stores it in a safety-deposit box and says he will never part with it.) Most of his discoveries, though, are more modest. Unlike many divers, who trade their loot to middlemen for resale, Eberlein works alone, selling about a thousand teeth a year through his Web site, megateeth.com. His regular buyers include a Canadian doctor, a Hollywood agent, an aviation engineer, a British lord, and Eberlein’s own dentist, who accepts the fossils as payment for checkups.

Not all Meg teeth come from underwater. Phosphate mines, for instance, are said to be fruitful sources. But teeth from soft, muddy creek beds tend to be easier to find, a veterinarian and collector named Gordon Hubbell told me, and they often have better enamel coverage, clearer serrations, and fewer chips. Hubbell ought to know: he has one of the largest paleodontal collections in the country, including around five hundred Meg teeth and “a couple of million” teeth from other shark species, which he keeps in a small museum behind his house. His devotion, however, does not extend to diving. “That’s too darn dangerous,” he told me, and few would contest it. Eberlein, who was once carried six miles out to sea while on a dive and had to be rescued by the Coast Guard, estimates that there are about two deaths a year in his field. This past May, one of his fellow-enthusiasts drowned in Georgia’s Broad River. By far the most famous casualty, though, was Vito Bertucci, a former jeweller from Long Island, who died in 2004. Bertucci began collecting Meg teeth as a teen-ager, in the mid-seventies. He found what may be the largest tooth ever—seven and a quarter inches—which he sold to Hubbell for only a few hundred dollars. “Every time he came back, he tried to buy it back from me,” Hubbell said. “I don’t think he realized the value of it at the time.”

Bertucci’s magnum opus was a reconstructed Megalodon jaw that he completed in the nineties. It was eleven feet wide and almost nine feet tall and used a hundred and eighty-two teeth. Four of them are longer than seven inches, an exceedingly rare size and a testament to Bertucci’s dedication. “You couldn’t talk to him about anything but sharks’ teeth,” John Woods, a longtime collector based in Savannah, told me. “That was his life.” Barker, a friend of Bertucci’s, agreed. “You could say, ‘It’s a nice day’—it led to sharks’ teeth. You could say your mother died—it led to sharks’ teeth. All roads with Vito Bertucci led to sharks’ teeth.” Bertucci drowned at the age of forty-seven, and when the authorities recovered his body from Georgia’s Ogeechee River, after several days of searching, they found a bag of teeth on him.

Back at the creek, Eberlein hauled himself up onto the stern of his small white boat. A black shorebird darted fast over the water, which glowed brilliant blue in the morning sun. Every now and then, a breeze swept along the banks, rustling through the green-gold marsh reeds and the tall, bushy trees laden with Spanish moss. Unlike many Meg-teeth collectors, who are attracted to the hobby by the thrill of owning something prehistoric, Eberlein says “the hunt is the fun part.” Still, he looked exhausted as Gene Ashley, his longtime boat captain and partner, removed his helmet, his gloves, and his mesh bags, which were plump with fossils. “The current’s picking up and it’s dragging me,” Eberlein said, sounding winded. Ashley extracted the teeth from the bags. One by one, he placed them on a seat. “That would have been a perfect tooth,” he said, smiling and holding up a large specimen that was sheared in half. It glistened oil-black in the sun, menacingly large, with little globs of pale mud in the cracks. Eberlein groaned and made a half-smile. “That would have been a nice, nice tooth,” Ashley repeated.

Brent Crane is a freelance reporter based in North Carolina.